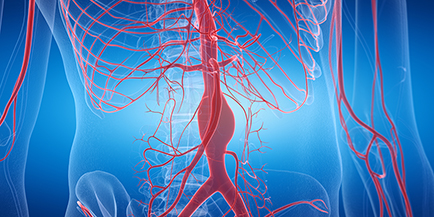

The heart is a hefty muscle. As such, it needs a hefty artery to handle all that blood it’s pumping. This is the aorta, which is the largest, strongest blood vessel in your body. Your aorta carries the oxygenated blood from your heart to the rest of your body but sometimes, due to age, genetics or poor cardiovascular health, the walls of the aorta distend and threaten to tear. This is called an aortic aneurysm. There are no symptoms, and complications can be fatal, earning this condition a rather infamous name as “the silent killer.”

First Physicians Group Cardiovascular Surgeon Kristen Walker, MD provides insights.

Click image for enlarged photo

What is an aortic aneurysm?

An aneurysm is any blood vessel that has expanded one and a half times its normal size or more. The average diameter of the ascending aorta is 2.5-3.5 centimeters, which means 4.5 centimeters equals an ascending aortic aneurysm.

Why is it a problem if the aorta widens?

It has to do with wall stress. Remember, the aorta is the artery that carries the oxygenated blood from your heart to the rest of your body. The first part of your aorta is the ascending aorta. Your heart is a strong muscle, so as it ejects the blood through your aortic valve, your ascending aorta actually distends to absorb the force of the blood being ejected. With each heartbeat, it expands and contracts. But the bigger it gets, the more the wall stress it endures which can, over time, actually weaken the aorta. If you have a connective tissue disorder, it may be especially weak and can tear.

It is natural for your aorta to get bigger with time—it does grow with you as you age—but it does not normally grow to aneurysm size.

How do aortic aneurysms develop?

The risk of having an aortic aneurysm does increase with age, because the longer you have that wall stress on your aorta, the bigger it gets. Other risk factors include high blood pressure, especially poorly controlled high blood pressure. To some extent, having high cholesterol can contribute to it.

Smoking is a really big risk factor. And there is a genetic component, at least in the thoracic aorta.

What is the genetic component?

Most aneurysms occur randomly but there are some families that have genetic abnormalities that make them at risk. If there are at least two family members with ascending aortic aneurysms, especially if a mutated gene is identified, then they have what we call a heritable thoracic aortic disease. Patients may have an abnormality of their aortic valve called a bicuspid aortic valve that puts them at risk of developing an aortic aneurysm. There are also specific connective tissue disorders that put you at very high risk of complications with an aortic aneurysm: Ehlers-Danlos, Loeys-Dietz, and Marfan’s disease. For all of those, we recommend patients be on a beta blocker—a medication that lowers your blood pressure and your heart rate, decreasing wall stress on the aorta.

The bottom line is that the most important risk factor is poorly controlled blood pressure so, even if you have an inherited abnormality of your aorta, the best thing you can do is maintain excellent blood pressure control.

What is an aortic dissection?

One of the most common complications that we see with an aortic aneurysm is called an aortic dissection. This is still incredibly rare, but becomes more common at larger size aortic diameters.

There are three layers to the aortic wall, and you can get a tear in that innermost layer, which then allows blood to seep in and dissect the layers apart. The blood travels down the path of least resistance into this place in between the layers of the aorta. And as it does this, it can block normal blood flow to your organs or it can weaken the outer wall and cause rupture. An aortic dissection in the ascending aorta is one of the few remaining cardiac surgery emergencies that we have.

Is there screening for aortic aneurysms?

Anyone who has an ascending aortic aneurysm should encourage first degree relatives to be screened. In addition, if a patient has a bicuspid aortic valve, meaning an aortic valve that has two leaflets instead of three, they should be screened at least once for an aneurysm. Frequently, however, aortic aneurysms are incidental findings. A patient will get a CT scan or an echocardiogram—an ultrasound of the heart—for another reason and they’ll notice that the aorta is enlarged.

How quickly do aortic aneurysms progress?

In general, they grow very slowly, only 1-3 mm a year. In patients with uncontrolled high blood pressure or connective tissue disorders, they may grow faster. In fact, accelerated growth is an indication to offer surgical repair of an aneurysm.

What does intervention typically look like?

Depending on which part of the aorta is affected, there may be either endovascular or open options. Endovascular procedures are usually performed through a needle stick or small incision in your groin. Open procedures are just how they sound, big open operations to replace parts of the aorta. There are endovascular procedures for abdominal aortic aneurysms. There is also a really good endovascular option to repair a descending or distal arch aneurysm.

But if the aneurysm is in the aortic root, the ascending aorta, or involves the first portion of the aortic arch–that’s about as big of an operation as you can get. This is what people generally consider open heart surgery. You come to the hospital, you undergo general anesthesia, and we go through the breastbone. We must put you on the heart and lung machine because we have to stop your heart to do the operation. Depending on which part of the aorta we’re operating on, we either replace it or repair it.

How do you decide between repair and replacement?

There’s not really a great way to repair the ascending and the arch so we remove it and replace it with a Dacron graft—a woven cloth with special properties that prevent it from leaking. It looks like the tube portion of a tube sock. Sometimes we can repair the root, if it is only slightly enlarged and the valve is not leaking too badly. If not, we have special grafts that allow us to replace the aortic root.

How can patients keep their aorta healthy?

Being vigilant about blood pressure control is the single most important thing patients can do to protect their ascending aortas. I frequently have patients tell me that they’re afraid to go to the gym because they don’t want to stress their aorta. I tell my patients with aneurysms that I want them exercising with low to moderate intensity exercises. It’s good for cardiovascular health. Patients with aneurysms should never lift heavy weights or do anything that causes them to strain, but use lower weights and higher reps is an excellent way to maintain overall cardiovascular and mental health.

Kristen Walker, MD is a cardiovascular surgeon with FPG and specializes in cardiovascular and aortic surgery. For more information about Dr. Walker or to make an appointment, click here.

Kristen Walker, MD is a cardiovascular surgeon with FPG and specializes in cardiovascular and aortic surgery. For more information about Dr. Walker or to make an appointment, click here.